|

In the 60s Germany lost its top spot in camera manufacturing to Japan. What the Japanese cameras perhaps lacked in imagination, they made up for it in quality, features as well as efficient production, hence price. The rest is history, Japan still dominates the camera market. Here's a short overview mostly going back to the early days of Japanese camera production. Note that one of the biggest brands, Minolta, has its own page on this site, and some more Japanese cameras (Picny, Gelto) can be found on the 127 film camera page, and finally, Japanese SLRs for the most part on my SLR page.

Semi Gelto

To start off with, a folding camera made by the same company as the Gelto 1270cameras shown elsewhere on this site (see link above in introduction). Half frame 120 folders, better known as 'Semi' cameras, were popular in Japan around WWII, and many camera makers produced them. Toakoki Seisakusho was no exception, although it appears they actually started their Gelto range first, as opposed to many other camera makers which started out with folding cameras.

The Semi Gelto was a pretty decent camera, it had for instance a shutter with a good range of speeds, a decent lens, body-mounted shutter release and a hinged wind knob. This may all sound trivial, but at the time it was a higher-end folder. It also showed the same high attention to detail characteristic for the Gelto 127 range. Clearly the latter were the more successful range, so the Semi was only in production for a few years and is in fact a lot rarer to find nowadays. A later model with metal top cover was also produced.

| |

A Semi Gelto I with Grimmel Anastigmat 75mm f/4.5 lens in Gelto-I shutter.

|

Samoca-35 III

Samoca cameras were made by Sanei Sangyo Co., later renamed to Samoca Camera Co. They started in 1952 with the rather quirky looking Samoca-35 series, the one shown below is the third incarnation. It was a very small camera, similar to the Beirette and Steinette/Hunter35/Primo range to which the camera showed some likeness. It had a rather limited range of shutter speeds but did feature helical focusing. It had a peculiar conical button on the shutter housing which needed to be pushed in to cock the shutter and release the wind lock mechanism.

Later versions had a flat top housing with automatic shutter cocking. A version with lightmeter, the E.M., was also made.

A Samoca-35 III with Ezumar Anastigmat C 50/3.5. The logo of the company, as seen on the shutter, consisted of three As arranged in a triangle; apparently inspired by the company name "Sanei", which can be phonetically understood as "three As" in Japanese.

Samoca 35 Super Rangefinder

Around 1956 a coupled rangefinder version of the Samoca-35 with an optional light meter was introduced, called the Super Rangefinder. Above the lens it had a small wheel which rotated whilst focusing, which indicated the focus distance but also moved the rangefinder mirror inside the viewfinder. A new addition was the switch between electronic and bulb flash. The rangefinder version managed to squeeze a lightmeter cell next to the rangefinder window and an exposure dial on the already crowded top plate. Certainly a lot of functionality in a small package!

A Samoca-35 Super Rangefinder with coated Ezumar D 50mm f/2.8 lens. It's missing its lightmeter flap.

Samoca M-35

Around 1958 Samoca started building cameras that were more conventional looking but nevertheless quite stylish, such as the M-35 below. It was a rangefinder camera with the viewfinder arranged right above the lens as to avoid any horizontal parallax. It had a wind lever and a Prontor-style shutter with speeds ranging from 1s to 1/300s. It had a 50mm f/3.5 Ezumar lens with helical focussing. A version with faster f/2.8 lens was the M-28, which was also sold in the USA as the Tower 57. A model with uncoupled light meter was called the LE, a later version with coupled light meter, f/2.8 lens and a more modern look the LE-II, also rebranded as Tower 57-A. The M-35 itself was also sold as the Hanimex A35 with Hanimar-branded lens.

The quite stylish-looking Samoca M-35 with Ezumar 50mm f/3.5 lens in a Synchro shutter presumably made by Samoca itself.

Top view of a Samoca M-35 with frame counter integrated in the wind lever and film reminder integrated in the rewind button.

Rebranded Hanimex A35 version of the Samoca M-35. The top housing inlays were white with a black border instead of plain black as on the Samoca version.

Samoca EE-28

The last of the Samoca cameras appears to be the EE range. It had an automatic exposure mechanism and the light meter needle was visible in the viewfinder. It also had a manual exposure mode. The build quality and finish appear of a lesser standard than the earlier models, and it was not much of a looker either.

A Samoca EE-28 with Samoca 45mm f/2.8 lens.

Oshiro Optical Works Emi-K

The Emi-K was produced in 1956 only by Oshiro Optical. It was a viewfinder camera with a 50mm f/2.8 Fujiyama Eminent Color lens, presumably that's why the camera was called Emi-K. It is nothing special and quite similar to other Japanese cameras from that era. Nevertheless, there is something I like about it. It was also sold as "Three C.s" and "Spinney". Very little it known about the company and also the origin of the Fujiyama lens is unclear, as the current lens maker Fujiyama says it was founded in 1975, two decades later. Oshiro also made the Hanimo 35 with selenium cell light meter.

Emi-K with a 50mm f/2.8 Fujiyama Eminent Color lens.

Shinano Lacon

The Shinano Lacon was a fairly obscure camera made during the early 1950s by the Shinano Camera Company, who also made the somewhat better known Shinano Pigeon. I must confess I was more charmed by the name than the actual camera, which is a straightforward viewfinder camera without many thrills, but in terms of looks clearly inspired by the Leica screwmount cameras, especially when viewed from above. The single viewfinder window looks oddly out of place in a top housing large enough to accommodate a rangefinder.

Functionally the Lacon was not that different from the Pigeon, both were simple viewfinder cameras with front cell-focusing lens, a leaf shutter with a limited range of speeds and a removable camera back to load film.

An early version with a small single viewfinder mounted directly onto the top plate also existed. The Lacon was later superseded by the Lacon C, which had a larger tophousing with integrated shutter release button but otherwise similar to its earlier incarnation.

A Shinano Lacon with Shinano Lacor 45mm f/3.5 lens.

Pal M4

The Pal M4 was made by Yamoto, a company that in the 1950s made a range of small and fairly simple 35mm rangefinder cameras that strongly resembled Leicas in appearance. The first one was the PaX, almost a miniature Leica II but with fixed lens and a leaf shutter. It was replaced with the PaX M2, still very much in Leica II style, and then the PaX M3, which had rectangular rangefinder windows and a lever wind, so arguably looked more like the Leica M3, although only vaguely. The next model, the M4, had an extra frosted window for the bright-line viewfinder. It was sold under various different names, including the Pal M4, an example of which can be seen below. It's a sympathetic little camera that was certainly well featured for its size, but like so many, the company disappeared without much trace in the early 1960s.

A Pal M4 with Luminor Anastigmat 45mm f/2.8 lens in unspecified leaf shutter. The camera feels quite similar to that of the Halina 35 (small but heavy), which at least in the UK is more commonly found.

Aires 35-III L

Aires Camera Works was a camera company from Tokyo that in the 1950s and early 60s had a great reputation, but whose name has nowadays slipped into obscurity. This is unfortunate, as the company made some impressive cameras. The 1957 Aires 35-III L was one of those. It was a coupled rangefinder with a bright-frame viewfinder of excellent build quality, it reminds me a lot of the Konica II that I reviewed recently. That said, they don't appear to have stood the test of time as well, the Aires nowadays are notorious for having problems with shutters and apertures, and mine was no exception. But then again, they weren't designed to last 60 years without much service. The highly-regarded six-element f/1.9 lens was one of the faster ones to be found on rangefinders from that era. Note that the L in IIIL stands for light value scale, which is what the camera used for setting its exposure. However, the implementation was a little awkward, as even though an aperture scale was indicated, it was never quite obvious which aperture setting the camera was actually using.

An Aires 35-III L with H Coral 45mm f/1.9 lens in Seikosha MXL leaf shutter. This example has a problem with a sticky shutter (I can see grease on the blades), whilst the aperture has a blade that does not move and again, there's grease on it. As these are commonly reported problems it appears Aires used a helicoid grease that was perhaps a little more volatile than others.

Top view of the Aires 35-III L showing a film reminder dial beneath the rewind knob, the rapid advance lever with the frame counter next to it. Also note the exposure setting ring on the lens with red LV numbers, which one had to pull back in order to select a different LV setting. Rotating the ring to select a different shutter speed would automatically adjust the continuous aperture to keep the exposure the same.

Aires Viscount

The 1959 Aires Viscount was essentially just a more modern looking upgrade of the Aires 35-IIIL above. It sported the same lens and it functioned very similar. It did have an extra frame in its viewfinder for use with a telelens attachment that could be screwed in front of the main lens. Like its predecessor, it was a heavy and solidly build camera of good quality.

Aires did build a whole range of other cameras, including TLRs, folding cameras as well as several leaf-shutter SLRs. The latter have been mentioned as the reason for the cameras demise, as it went bankrupt a few years later.

An Aires Viscount with H Coral 45mm f/1.9 lens in Seikosha SLV leaf shutter.

Mizuho Six

Neoca was yet another small Japanese camera maker founded after WWII, and initially (in the early 1950s) specialised in medium format folding cameras under the name Mizuho that were quite similar to contemporary folders by other brands such as Olympus. The line-up included both viewfinder as rangefinder models. One nice feature of the Mizuho Six was that they had an internal 6x4 mask in the form of two hinged flaps inside the film chamber. To accommodate the use of the 6x4 format the cameras also had an extra red spy window and a colour mask in the viewfinder, although the latter wasn't that useful as the edge of the viewfinder frame isn't in sharp focus when looking through it.

An original Mizuho Six (i.e., Six I) with Mizuho Koki Militar Special 80mm f/3.5 lens in MKS shutter. An MKS logo is also engraved on the struts, so presumably all components were made in-house.

Detail of the top plate of the Mizuho Six.

Neoca 2S

Neoca was a small Japanese camera maker starting initially under the name Mizuho (see above), but from 1954 it started to make 35mm cameras under the name Neoca. The early models had a characteristic metal front plate with rectangular range and viewfinder windows, perhaps in an attempt to make it look like the Nikon rangefinders. The Neoca 2S below was one of these. A particular feature was that it was a double-stroke camera. but it did have the advantage that it cocked the shutter automatically. The lens had a very close focus range of 0.5 m. Rather unusual also was that the shutter was located behind the lens.

A Neoca 2S with Neokor Anastigmat 45mm f/3.5 lens. I am not sure if Neoca made these lenses theirselves, there were many lens makers that sold their lenses to various camera makers. The Neokor is one of the few lenses from that era that had a close focus range of only 0.5 m though.

Top view of the Neoca 2S.

Neoca-S

Following on from their IIIS, Neoca modernised their camera range, starting with the IV-S, which was much more sleek-looking and had a large bright-frame viewfinder window, and then the S, SV, and the Robin, which appears to be identical to the SV. The latter three were commonly equipped with Neokor f/2.8 lenses, but could also be had with the rather legendary Zunow lenses (see Walz 44) either in f/2.8 or f/1.8 apertures. The various Neocas were attractive and high-quality cameras, but I am not aware of any Neocas with a lightmeter. Instead, after the SV it brought out the 35K, a camera with slower lens, less shutter speeds and no rangefinder. Perhaps this lack of innovation and move to cheaper cameras became fatal in the end, as soon the company disappeared without much trace.

A Neoca S with Zunow Opt. 45mm f/1.8 lens, the colouring of the front element suggests it is multi-coated (the glass itself is clear).

Top view of the Neoca S showing the frame counter, which automatically reset to zero when opening the camera back, and film speed reminder dial.

Beauty Lightmatic SP

Beauty is a long gone Japanese camera brand, one of many to suffer under an increasingly competitive market, despite building a good reputation. During its short existence it did make an interesting range of cameras that included 16 mm cameras, medium format TLRs and an SLR (akin the Reflex Korelle) as well as a line of increasingly well-specifed 35mm cameras. The early 1960s Lightmatic SP was one of the latter, if not the last. It was an attractive-looking rangefinder with a fast Biokor f/1.9 lens with integrated lightmeter, and one of several very similar models produced by Beauty. There is an (almost?) identical model called the Lightomatic III and several models with the lightmeter mounted on the camera body, such as the Beauty LM, the Super L, and confusingly, a Lightomatic. No doubt there were more! I am not sure where the designation SP on this model referred to, if it was like the Olympus 35 SP it would have a spot metering mode but I don't think it has.

A Beauty Lightmatic SP with six-element Biokor-S F.C. 45 mm f/1.9 lens in Copal SV shutter with a range of shutter speeds from 1 to 1/500 s. This camera had a jammed focus helicoid when I got it but this wasn't too hard of a repair. As usual someone had been in there before though and snapped the lightmeter cables. Oh well.

Not much information can be found about the Biokor lenses on the various Beautys, but one source suggests the f/2.8 Biokors were made by Tomioka, well known for it's Lausar TLR lenses, but not really known for any fast 45mm lenses, so I am not convinced they made the f/1.9 model. I have only two other 45/1.9s in my collections, a Coral on an Aires and a Fujinon on a Fujica. Could the designation F.C. on the Biokor stand for Fuji Co.? Or has it something to do with coatings? The jury is still out, so any info would be appreciated!

Togodo Toyoca 35

This is about the Togodo Toyoca 35, not to be confused with the Tougodo Toyoca 35, which was a completely different camera (a horizontal 35mm TLR!), or the Tougodo Toyaca 35-S, a 35mm viewfinder camera. It appears in fact that the Toyoca 35 was the only camera made by the Togodo Optical Company Ltd, a manufacturer about which I have not been able to find any information. I have found reference to a Toyoca Six by the same company, but all it said is that it was not available in the U.S. There is an image of a 6x6 Toyoca on the internet, claiming to be a Toyoca Six by Togodo, but it is clearly made by Tougodo instead.

Togodo Toyoca 35 with Tomioka Lausar 45mm f/2.8 lens.

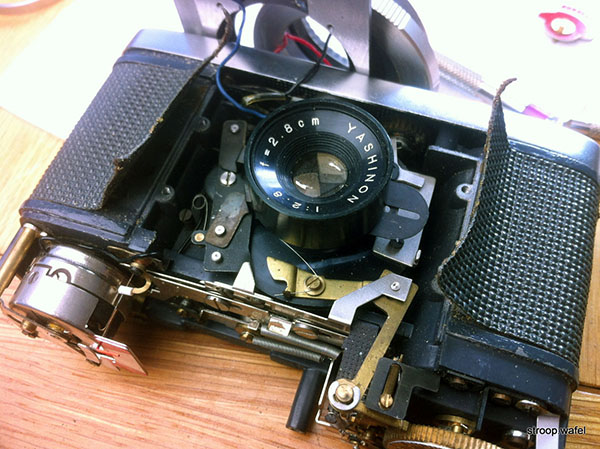

In any case, the Togodo Toyca 35 was an unremarkable but decent quality rangefinder from Japan produced in the mid-1950s. It had a shutter of unknown make, possibly NKS, without flash synchronisation but with a selftimer and a decent range of speeds (1 s - 1/300 s). The rangefinder was coupled to the helical focus mount. Probably the most interesting aspect was the lens, which was a Tomioka Lausar 45mm f/2.8. Tomioka was a well-known Japanese lens maker, in fact they build most if not all Yashica lenses (yes, the Yashinons, the Yashikors, etc.). The Lausar was the Tomioka version of the Tessar, so a four-element lens.

Interestingly, the Toyoca shows some remarkable similarities to the Taron 35, the first camera by Nihon Kosokki, later renamed to Taron after its camera line, and producer of NKS shutters. So which company actually build these cameras remains unclear to me.

Top view of the Togodo Toyoca 35.

Mamiya 35

Mamiya is one of the better-regarded Japanese camera makers and still exists today. Although primarily known for its medium-format cameras, it has also produced a wide range of rangefinder cameras, starting with the Mamiya 35 series in the late 40s, early 50s. This model was very similar to other first models of several Japanese camera makers, such as the Konica I, the Olumpus 35 and the Topcon 35. They were generally well made, small but heavy 35mm cameras with high-quality lenses in helical focus mounts and with excellent shutter, wind knobs (not levers) with integrated frame counters and simple rangefinder without framelines, but rapidly evolved to more fancy models of which many examples can be seen on this page.

The first version of the Mamiya 35 was a bit of an oddball though, it looked more like the Konica I than the next version shown below, but had an odd focussing system where the filmplane moved instead of the lens. Also, it had a Konica lens, one of the few (or only?) Mamiya cameras to come without the standard Mamia-Sekor lens. The next version was introduced six years later in 1955, originally with an f/3.5 lens but from 1956 with an f/2.8 lens like my example below. The third version has a wind lever and a slightly larger top housing. It was avaliable with either a f/2.8 or a fast f/2.0 lens. Like Olympus, Mamiya also produced a version with 35mm wide angle lens, the Mamiya Wide.

Mamiya 35-II rangefinder camera with Mamiya-Sekor 50mm f/2.8 lens in Seikosha-MX shutter. The camera is well constructed and much heavier than its size suggests, but the chrome plating on the top housing is rather thin and wears easily, as can be seen between the two rangefinder windows.

Mamiya Magazine 35

In 1957 Mamiya introduced a rather unusual camera, the Magazine 35, which on first glance looks like many other rangefinders of that era, but it had a trick up its sleeve: an interchangeable back. Basically, the camera body could be separated from the top housing and lens without any light leaks, so one could change film speed or type without needing to rewind the film (provided one had an additional camera back).

Although in theory a great concept, the camera was not very popular due to its very high price and the fact that the backs themselves cost about half the price of the camera itself, and you needed at least one extra back for the system to be of any use. Not many other cameras with interchangeable back have been made, the Kodak Ektra, Adox 300, plus some Zeiss Ikon Contarex and Contaflex models, none of them being particular popular. Perhaps professional photographers would carry multiple with different around, perhaps even more convenient than having to change camera backs, whereas amateur photographers did not really have the need? Nevertheless, an interesting piece of camera history.

A Mamiya Magazine 35 with Mamiya-Sekor 50mm f/2.8 lens in Seikosha-MXL shutter, a Compur-Rapid clone. A fairly plain looking but heavy, high quality rangefinder with interchangeable camera back. The back could be removed by turning the red locking knob at the bottom of the back, which would first close the metal plate covering the film gate (see top photo) and then release the back itself. The back also had a rewind knob, note there is none present on the cameras top housing.

Mamiya Ruby Standard

In addition to innovative experiments like the Magazine 35, Mamiya produced several more regular rangefinder models, such as the Mamiya Crown, Metra and Ruby. The latter was first introduced in 1959. It was a rangefinder camera which featured a selenium-cell meter and a Mamiya-Sekor 48mm f/1.9 or f/2.8 lens, later production (apparently called the Mamiya Ruby Standard) had a Mamiya-Kominar 48mm f/2 lens. It's most distinctive feature was the film speed dial on front of the camera. Different Mamiya models are a little hard to identify as the names were generally not indicated on the camera bodies, and little information is available about them, let alone instruction manuals. However, Butkus has a manual for the Tower 18A, which was a rebranded version of the Mamiya Ruby with f1/.9 lens.

A 1961 Mamiya Ruby with Mamiya-Kominar 48mm f/2 lens. This exact version was also sold as the Tower 18B.

Top view of the Mamiya Ruby.

Rank Mamiya

The Rank Mamiya introduced around 1963 was a cheaper version of the Mamiya Ruby. It was also known as the Mamiya 4B but was sold under the name Rank in the UK. Compared to the Ruby it had a slower and wider Mamiya-Sekor 40mm f/2.8 lens, somewhat comparable to the Minolta Uniomat but without exposure automation.

Mamiya 4B rebranded as Rank Mamiya.

Canon Demi

Canon as a company will need little introduction, as it still is the largest camera maker in the world. The company was a relatively late starter, founded not long before WWII, but it rapidly became a major force due to its high-quality but affordable cameras. One of these was the 1963 Canon Demi. It was a half-frame camera, like the Minolta Repo, which would take 135mm film but used a smaller film format and would therefore fit more photos on a single film roll.

The Canon Demi was a manual camera with a limited range of shutter and aperture options, which were controlled by a single setting ring. On top of the camera was a lightmeter read out where one had to match two needles to get the correct exposure. One needle was controlled by a large selenium cell and indicated the amount of available light, the other needle was adjusted by turning the exposure ring.

The funky-styled Canon Demi with 28mm f/2.8 lens (equivalent to 40mm on full frame) in Seikoshi shutter. Note the small round viewfinder window right above the lens, which was a Keplerian viewfinder as described below.

An unusual feature of the Canon Demi was its Keplerian viewfinder. Most cameras from that time had reverse Galilean viewfinders, which was essentially a two-lens telescope turned backwards, which gave a wide angle view. The basic version of a Keplerian viewfinder also had two lenses, but they were further apart and importantly, the focal point of the front lens was inside the viewfinder. By putting a mask at this focal point one would get a viewfinder image with sharply defined edges, in contrast to the Galilean viewfinder which had fuzzy edges and framing was therefore more inaccurate.

The drawback of the Keplerian viewfinder was that it inverted the image. On the Canon Demi this was corrected by the use of prisms. Therefore, the viewfinder window was offset relative to the eyepiece. Turret-style viewfinders as well as the Leica multifinders such as the VIOOH used a similar design.

|

Rear view of the Canon Demi. A little peculiar was the focus distance scale at the back. |

|

Interior of the Canon Demi. Note the small vertical film frame, typical of half-frame cameras. |

|

Top view of the Canon Demi, showing the match needle lightmeter. If you look carefully you can see that the viewfinder window is offset relative to the eye-piece. |

Quite a few versions of the Canon Demi were produced, including the Demi-S with faster lens and a larger exposure range, and the Demi-C with interchangeable lens for which a 50mm f/2.8 telelens was available. Later the automatic exposure Demi EE range was introduced. Early models had a selenium cell around the lens, later models had a CdS sensor where previously the viewfinder was located, and a brightframe viewfinder where the selenium lightmeter cell used to be.

Konishiroku (Konica) Pearl

Konica is a company with a very long history in photographic materials, but probably best-known for taking over Minolta when it failed but soon after killing off the camera product line. Konica-Minolta is now a well-respected producer of photocopiers.

The company started making 35mm cameras just after WWII with a range of classic-looking rangefinders (branded Konica), but it appears to be a little known secret that it also made several folding cameras, the Pearl range, a long time before. At the time the company was still called Konishiroku. It was only simplified to Konica (short for Konishiroku Camera) much later, adopting the name of its 35mm range.

The Pearl range included rollfilm cameras that used 120 or 127 film with a variety of frame sizes. The 1949 Pearl I was developed from the Semi Pearl, 'Semi' indicating a half frame camera with a 6x4.5 cm frame format on 120 film. It had several interesting features, such as a key to wind the film at the bottom of the camera, a unit-focussing lens mount and an uncoupled rangefinder. Later models had a coupled rangefinder.

Konishiroku Pearl with Hexar 75mm f/4.5 lens in Durax shutter. Note the lack of any wind knobs on top of the camera, as it has a wind key at the bottom.

Konica I

The 1947 Konica I (at the time simply known as Konica, without the I) was Konishiroku's first 35mm camera. It shared several features with early Leicas, such as the retractable (but not interchangeable) lens with helical focus, the (excellent quality) rangefinder and the wind knob with frame counter, but the similarity ends there as the Konica had a leaf shutter and a rear door that could be opened to load film. Also, the shutter release was on the shutter itself, which needed to be cocked by hand. Thus, the camera had no double-exposure prevention.

Several cosmetic variants existed, detailed on the excellent Konica I-II-III camerawiki page. The example below is a Type B as it has the name Konishiroku embossed at the back and the serial# engraved on the top housing. The lens was a 4-element Hexar, initially available with f/3.5 aperture, but later a f/2.8 version could also be had. The last version had an f/2.8 Hexanon. The shutter was a Konirapid, very similar to a Compur-Rapid, later updated to the Konirapid-S with flash synchronisation.

Konica I type B with coated Konishiroku Hexar 50mm f/3.5 in Konirapid shutter from around 1948. This example is missing some of the leatherette, which was rather brittle and peels off easily.

(left) Back side of Konica I with company name embossed in the leatherette. (right) Top view of the Konica I showing the extended collapsible lens.

Konica II

The 1952 Konica II was the successor of the Konica I above and quite a step up in quality. In fact, I think this is one of the finest and best-built Japanese leaf-shutter rangefinders, easily competing with its German equivalents. Compared to the Konica I had a body-mounted shutter release, an accessory shoe (which was curiously missing on the Konica I) and a higher contrast rangefinder than the already very good one on the Konica I. It also had a separate T button on the front plate. On the downside, the shutter still needed to be cocked manually. The lens was still retractable, but instead of giving the lens a small twist and then push it in (like on most other cameras with retractable lenses), on the Konica II one had to pull a little lever on the focussing knob at the infinity setting, after which the knob could be rotated further, thus retracting the lens fully. The Konica II had a much more modern look than the fairly spartan Konica I, with wind knobs with integrated frame counter and film reminder dial, an eye-catching curved front plate and a metal bottom plate. The door catch was perhaps even a little over-engineered, after rotating a ring similar to the one on the bottom plate of a Leica screw-mount camera, one had to push in this ring to release the catch that opened the rear door.

As with the Konica I, several cosmetic variants were available, including a version with Hexar lens that was missing the T knob. Early production had a Konirapid-S shutter, later replaced by Konirapid-MFX or Seikosha-MX shutters. The top model, the Konica IIA, had a six-element f/2 Hexanon lens.

The magnificent Konica II with its excellent five-element 50mm f/2.8 Hexanon, which had a yellow-brownish coating instead of the more common purpley-blue one on the Konica I and most other contemporary cameras. The accessory shoe has an engraved diamond with the letters EP in it, indicating that this was an export model sold at one of the Allied Army military bases in Japan. I love the look of this camera and was very pleased to finally get my hands on one!

Top view of the Konica II showing off its impressive lens-shutter assembly.

Konica III

The next model was, unsurprisingly, the Konica III, introduced in 1956. It had undergone quite a few changes, most notably the film advance mechanism, which was operated by a lever on the lens mount instead of a wind knob. The lever had to be pushed down twice to advance the film as well as automatically cock the shutter, as system also found on the Zeiss Ikon Tenax and the Agilux Agimatic. The lens itself was no longer retractable, so the camera turned out a little bulkier than the Konica II. New was also the Leica IIIf-style self timer on front of the camera. Essentially the same was the fairly small rangefinder. The main selling point of the camera, however, was its magnificent six-element f/2 Hexanon lens.

A Konica III with its superb six-element 48mm f/2 Hexanon lens in Seikosha-MXL shutter.

Top view of the Konica III.

Konica IIIA

A few years after the Konica III the Konica IIIA was introduced, which has a much larger and brighter viewfinder with a projected frame which adjusted for parallax as well as change in field of view during focussing. The styling was also a little different, especially the lens base, which certainly looked less elegant with a confusing amount of numbered rings. A new feature was the fold-up rewind lever. The Konica III was available with a 50mm f/1.8 lens in addition to the f/2 version found on its predecessor.

The final incarnation of this series of Konica cameras was the Konica IIIM equipped with coupled selenium lightmeter. It also had a peculiar option to function as a half-frame camera, which turned the standard lens essentially into a short telelens.

A Konica IIIA with fast 50 mm f/1.8 Hexanon lens. This example has some damage, there's a small dent in the top and a fracture in the viewfinder prism. I call it a covid victim, as the reason for the damage is that my wife didn't want me to touch the box it arrived in, opened it herself, and the camera dropped straight out, onto the floor. I think she reckoned I'd catch it?

Top view of the Konica IIIA, showing small changes to the top of the camera and the various numbered rings on the lens-shutter assembly. A bit cluttered perhaps, but at least all visible from the same angle, unlike on the Konica III.

Konilette 35

OK, and then there was a Konilette 35. A bit of a let-down after the delights of the early Konicas above, but clearly aimed at a different market. It was introduced in the late 50s around the same time as the Konica IIIA. The Konilette 35 was a simple viewfinder camera of medium build quality with a (presumably three-element) front-cell focussing f/3.5 Konitor lens with unmarked shutter having a limited 1/25-1.200 range. It had a Retina style clasp to open the rear door and featured a lever wind. In the top housing it had a frame counter as well as a rather flimsy looking accessory shoe. Although the viewfinder looks as though it may be of the bright-frame type in fact it isn't, it is a simple Galilean type without a frame.

Konilette 35 with Konitor 45mm f/3.5 lens and its dedicated lens hood.

Konica Auto S2

Around 1959 Konishiroku introduced the Konica S, a rangefinder with a modern look and a light meter. This evolved into the camera pictured here, the Auto S2. This 1965 camera was all about the lens, a six-element fast f/1.8 Hexanon, although it was also well-featured otherwise, including a parallax-corrected coupled rangefinder, automatic exposure as well as a manual mode, and a Copal SVA shutter with a range of 1 - 1/500 s. Note that this was the first Konica that no longer had the company name 'Konishiroku' marked on the lens.

Konica Auto S2 with fast Hexanon 45mm f/1.8 lens. Mine rattled and was loose, so I had to open it up only two find two loose screws inside.

(left) Hexanon 45mm f/1.8 lens with front ring removed. Some cleaning marks visible on the front element. (right) Prontor-style Copal SV shutter.

Hexanon lenses have always had an excellent reputation and Konica was obviously aware of this, using the lens design as the main feature on the box for the Auto S2. It was a six-element lens in four groups, a double-Gauss design similar to the Schneider Xenon and Zeiss Biotar.

Konica C35 V

Soon after, Konica, like many other companies, turned their attention to smaller, more portable cameras. In 1968 it introduced the C35, less featured than the S2 but a lot smaller and very successful, surviving in several incarnations until the 1980s. The one here is the 1971 C35 V, which presumably stands for viewfinder, as that's what it has instead of the rangefinder on the regular C35. However, it does have a nifty little extra window in the viewfinder that shows the zone focussing symbols, so the rangefinder is not too badly missed. This feature appears to be copied from the Minolta Hi-Matic C.

A chrome Konica C35 V with funky green leather featuring a Hexanon 38mm f/2.8 lens. I really need to give it the clean-up it deserves! I don't think the leather cover is original

Konica Auto S3

The 1973 Konica Auto S3 was the successor of the Auto S2 above and incorporated quite a few changes. First of all it was a lot smaller. This was a trend at the time, Minolta did a similar thing with the introduction of the Hi-Matic E, F and G following up from the Hi-Matic 7s, 9 and 11. In fact, the Minolta Hi-Matic 7SII and Konica Auto S3 were remarkably similar cameras, and it has been argued that both were made by Cosina (for which I have seen no convincing evidenec). There were subtle differences. The Auto S3 had an adjustable fill-flash system aided by the lightmeter, but only had shutter priority automatic exposure control, so no manual mode like the Hi-Matic 7Sii had. Also, the lens was a little wider (38mm vs. 40mm, so nearly a true wide-angle len) and presumably made by Konica themselves. It was a six-element lens with a fantastic reputation.

Konica Auto S3 with Hexanon 38mm f/1.8 lens.

A little surprisingly, the Auto S3 more or less ended production when the Hi-Matic 7sII was introduced, so they were never direct competitors. Perhaps the Minolta and several related models by Vivitar, Revue and Prince (see my Minolta page) were simply 'inspired' by the Konica. Also note that in Japan the model was sold as the Konica C35 FD. This was also available in chrome instead of the black-only Auto S3, so if you fancy a chrome Auto S3, now you know what to look for.

Top view of Konica Auto S3 with Hexanon 38mm f/1.8 lens.

Riken Ricoh "35" S

Ricoh is another Japanese camera maker that still survives today. In fact, I used to have one of its earlier digital endeavours, a Caplio R4. A capable little shooter but it didn't nearly survive as long as many of its non-digital predecessors.

The company was originally called Riken, with Ricoh being the name of its cameras. Its first camera was the Riken No.1, an unusual Leica-style focal plane camera but for 127 film. It also made several folding vest pocket and TLR cameras. The Ricoh 35 was its first 35mm camera, introduced in 1955, although perhaps it was preceded by the Ricolet, which was a viewfinder version of the Ricoh 35. The 1950s were a decade of great progress in camera technology, but because it was still early days, camera makers were still experimenting with their designs. The Ricoh 35 was no exception and it had a rather unusual feature: a rapid wind lever integrated into a removable camera back. Not only that, the lever was also foldable. The camera could also be wound be a more traditional wind knob.

A 1957 Ricoh "35" S with 45 mm f/2.8 Riken Ricoh lens, which was apparently made by Tomioka and had five elements in three groups, although I haven't confirmed that personally - it would be unusual for a f/2.8 lens. The shutter was made by Riken itself and wasn't of the standard of the rest of the camera and had a limited range of 1/20-1/200s.

A number of fairly similar models was produced in a short time span of only a few years, including the 35, 35S, 35 De Luxe, 500 (different from the later 500 series, see below) and the Five-One-Nine.

Other than that the camera was unremarkable but well build and specified, having a helical focus mount and coupled rangefinder.

Top view of the Ricoh "35" S. The body of this camera was unusually wide, and I am not quite sure why they designed it that way: for better ergonomics to hold the camera, or to fit a rangefinder as well as a double wind mechanism?

The removable back of the Ricoh "35" S, showing the foldable wind lever. As long as one didn't need to change exposure or focus, the design did allow you to shoot photos very rapidly.

Ricoh 800 EES

Ricoh's most well-known line of cameras was the Ricoh 500 series, which started as a classic-looking rangefinder but evolved into an extensive range of compact cameras, the 500 G being the best-known model. The Ricoh 800 EES from around 1974 had a highest shutter speed of 1/800, to which is thanks its name, faster than the typical 1/500 on other cameras including the Ricoh 500 G. It was a rangefinder with fully automatic exposure. Apparently it was also sold as the Elnica F although I don't have one so I can't confirm it is identical.

A Ricoh 800 EES with 40 mm f/2.8 Rikenon lens and fast 1/800s top shutter speed.

Ricoh Auto Shot

Ricoh also produced some more exotic cameras, like the Auto Shot. At first glance it looked like it was missing a viewfinder until you realised that it was integrated in the light meter cell surrounding the lens. It was also not immediately clear what was the top and what was the bottom of the camera, as the wind knob and strap lug were at the bottom. Wind knob, one may ask? Did not all cameras of that era have wind levers? Yes, but this little camera had in fact a motor wind!

Despite its small size it did shoot 36x24mm pictures on standard 135 film. In automatic mode it had a fixed shutter speed of 1/125 s with the aperture being controlled by the light meter. The camera could also be operated in manual mode by selecting the aperture, the shutter speed was 1/30 s in that case.

The Ricoh Auto Shot. Apparently it came with a lens cap that would double as a flash unit but unfortunately this example did not.

Top view of the Ricoh Auto Shot. Apparently it came with a lens cap that would double as a flash unit but unfortunately this example did not.

Fujica Rapid D1

Fuji (nowadays called Fujifilm) is a photographical company with a long history and one of the few that still produces photographic film today. In fact that's how the company started in 1934. It started producing cameras after WWII under the name Fujica, including a fair amount of compact cameras. It entered the Rapid camera market in 1965 with several models, including the Rapid D1. Like the Ricoh Auto Shot above, it had a motor wind but had a more classic look. It could shoot in automatic as well as manual mode.

A Fujica Rapid D1 with 28mm f/2.8 Fujinon lens.

Inside of the Fujica Rapid D1 showing its small half-frame film gate.

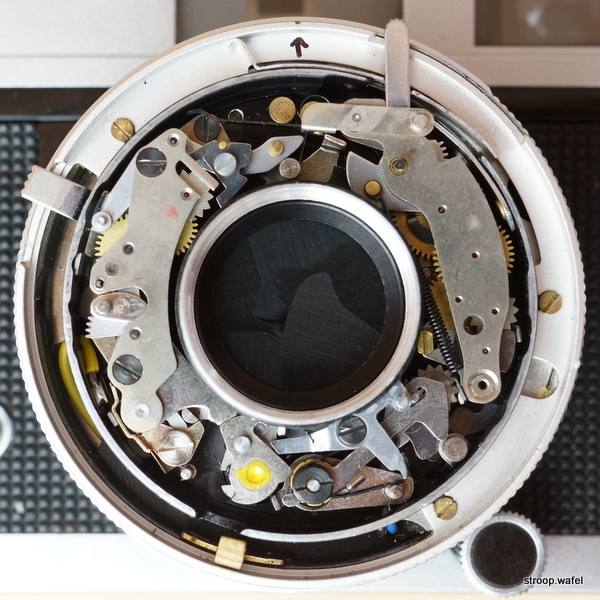

Fujica Rapid D1 with dismantled lens to get to the shutter. Fujicas had a good reputation but this shutter does little to impress me.

Fujica 35-EE

The Fujica 35-EE was introduced in 1961 and boasted to be the first camera with three exposure modes: automatic, semi-automatic and manual. Available light was measured using a selenium cell, the 'Electronic Eye', hence the name EE, a common name at the time and already seen several times on this page. Automatic exposure did not, however, mean full automatic control, as in Auto mode the camera would basically function in shutter-priority mode: it would automatically select the correct aperture based on the light values as measured by the lightmeter. If light was insufficient, a red dot would appear in the viewfinder window. In semi-automatic mode, one could read the correct aperture in the lightmeter window, but this aperture setting still needed to be set manually. The camera also had an early implementation of an auto exposure lock, as the aperture setting would be fixed by pushing down the shutter release button halfway. In principle one could reframe and refocus the image whilst keeping the exposure fixed.

A Fujica 35-EE with fast 45mm f/1.9 Fujinon lens.

Fuji was a company that liked doing things slightly differently, which was also evident on the Fujica 35-EE. To focus the camera one would turn a thumb wheel at the back of the camera, a setup quite similar to the Voigtlander Vitessa. Turning this wheel would focus the lens by moving it in and out as a single unit without rotating it, as well as move the rangefinder and the parallax corrected viewfinder frame. The rewind lever could be found at the side of the camera instead of at the top, whereas the auto-reset frame counter was found at the bottom of the camera. A ring around the lens base that looked like a focus ring was in fact the shutter speed setting ring. To get to slow shutter speeds (slower than 1/15) one needed to push a little button at the front of the camera, presumably to avoid camera shake by selecting a too slow shutter speed by accident while using automatic mode.

The Fujica 35-EE was preceded by the less automated 35-SE and superseded by the more automated 35 Auto-M. In addition Fuji made a small range of interesting half frame and rapid cameras, like the Rapid D1 above.

Two auxiliary lenses were also available for the Fuica 35-EE, a 35mm wide angle and 85mm telelens. These lenses would simply screw onto the filter ring of the standard lens, but had a complicated way of focussing: one needed to read of the focus distance on the distance dial on top of the camera and then adjust the focus to match the conversion scale printed on the lens. About as cumbersome as the auxiliary lenses of the Kodak Retina C cameras, although at least one did not have to remove the front cell of the standard lens first! Both auxiliary lenses came with their own parallax-adjusted viewfinder.

Taron PR

A lesser well known Japanese camera manufacturer was Nippon Kosokki, which started off as the producer of NKS shutters, but in the 1950s and 60s ventured into cameras: the Taron, a range of well-build but fairly standard rangefinders. Their biggest claim to fame was undoubtedly being the first to introduce a camera with CdS lightmeter (the 1962 Taron Marquis, see below). The 1959 Taron PR did not have a lightmeter, just a rangefinder, but because of its sleek lines I find it one of Taron's more attractive looking cameras. The lens was nothing special, a 45mm f/2.8 Taronar and a fastest shutter speed of 1/300 was also nothing to impress. Nevertheless, it was a well-build camera and perfectly adequate for most people. For the more demanding photographer there was the Taron VR with brightframe viewfinder, a faster f/2 or f/1.8 lens and a faster top speed of 1/500, or the VL if you wanted a lightmeter. The Taron PR also appeared as the Nasco Galaxy with a slightly modified top housing.

A Taron PR with Taron Taronar 45mm f/2.8 lens in Citizen-P shutter. It is a little curious that a company that made shutters would use some other company's shutters on their cameras, but only the very first Taron model, the Taron 35, had an NKS shutter. Clearly they had no great confidence in their own product, or decided that more money was to be made with cameras.

Taron Marquis

The 1962 Taron Marquis was the first camera to be equipped with a CdS lightmeter, which were more reliable and smaller than selenium cells but needed a battery to work. The battery voltage could affect the light readings (unless special circuity was built in), which may cause compatibility problems with modern batteries, as the original mercury batteries have been phased out due to environmental concerns. It wasn't long before other companies followed suite, e.g., Minolta introduced the Hi-Matic 7 not long after, the first camera which had the CdS mounted on the lens barrel.

Apart from the innovative lightmeter the camera was comparable to its many competitors, being a fully manual camera with a fast f/1.8 multicoated lens, shutter with a wide range of speeds of 1 to 1/500 s and a decent rangefinder. However, it did show exposure indicators in the viewfinder, indicating which way to turn the aperture control for the selected shutter speed. The Marquis was also rebranded as 'Rival', even though it was available under its original name outside Japan also.

A Taron Marquis with Taron Taronar 45mm f/1.8 lens in Citizen-MVL shutter, the first camera with CdS lightmeter.

Yashica YK

Yashica started making cameras in the mid 1950s. The Yashica YK was the follow up of the Yashica 35, a high-quality rangefinder which was inspired strongly by the design of the Nikon rangefinders, but unlike those, sporting a fixed lens and a leaf shutter. The YK was introduced at the end of the 1950s and was in some ways a downgrade compared to its predecessor, lacking slow shutter speeds and only available with an f/2.8 aperture lens, but not a bad camera in itself. It had a sister camera, the YF, which was more advanced but decidedly less attractive looking. However, the heydays of the brand were still to come, see in particular their TLR cameras elsewhere on this site.

A Yashica YK with Yashinon 45mm f/2.8 lens in Copal shutter. A fairly middle of the road camera for a Japanese rangefinder from that time, not bad, but nothing special.

Yashica Mimy

The cute little Mimy was the most basic of several half-frame Yashica models. Half-frame cameras (18x24mm, half the size of the 35mm format but using the same film) had a brief spell of popularity in the mid 1960s; other examples on this site are the Canon Demi and Minolta Repo. The Mimy was essentially a dressed-down version of the Yashica 72-E (see below). Like the 72-E it was a viewfinder camera but with fixed focus and without manual exposure controls. Due to the short focal length of the lens (28mm, equivalent to about 40mm on full frame) the depth of field was relatively large, which was why Yashica could get away with a fixed focus lens. The focus distance was set at 3m, so one needed to stop down to at least f/11 to get infinity focus. Thus, this camera was more practical for street photography.

The Mimy was equipped with auto exposure: upon pushing the release button half-way down the bottom left corner of the viewfinder frame would change from red to yellow if light was sufficient. The camera could also run in aperture-priority mode, although it appears this was mainly meant to be used with flash, as the lightmeter window did not clearly indicate if the exposure was fine. Film was advanced by means of a small thumb wheel at the bottom of the camera. The Mimy was succeeded by the Mimy-S, which had a redesigned viewfinder area and a lens that could be focussed.

A Yashica Mimy with fixed-foxus 28mm f/2.8 lens.

The innards of a Yashica Mimy with its front removed. The aperture is set by moving two metal slits in opposite directions to form a diamond-shaped iris, one of the slits is visible just to the right of the lens. On this example the two slits had stuck together, probably due to lack of use, but after loosening them up this little Mimy was once again working as it should.

Yashica 72-E

The Yashica 72-E looked similar to the Yashica Mimy about but had the advantage of a lens with adjustable focus as well as manual exposure control. It had a uncoupled lightmeter, so one had to manually transfer the exposure readings to the shutter. It did not have any auto exposure modes like the Mimy. The name 72-E was derived from the fact that one could make 72 exposures on a single 36-exposure roll of 35mm film. Yashica must have meant this as a selling point, but personally it would put me off! Of course one could buy film with fewer exposures if making 72 photos seemed intimidating. Considering the camera was mainly meant to be fun and portable to make snapshots I'd probably have gone for a more likeable name, like indeed the Mimy.

A Yashica 72-E with Yashinon 28mm f/2.8 lens in Copal shutter.

Yashica Electro 35

The Yashica Electro 35 range was a series of rangefinder comparable to the Minolta Hi-Matic range, pairing fast high-quality lenses with easy-to-use camera bodies and fully automatic exposure. The first model was introduced in 1966, followed in 1968 by the Electro 35 G and later the GS and GSN. These were the models with chrome bodies, the GT and GTN were the black versions.

The camera had an automatic aperture priority mode, which means it selected the shutter speed based on the aperture setting, film speed and the available light as measured by a CdS meter. The camera had orange and red warning lights visible in the viewfinder as well on top of the camera. The first warned that shutter speed was too low for hand-held exposures, the second for overexposure.

The first model of the Yashica Electro 35 range, sporting a fast Yashinon 50mm f/1.7 lens.

Top view of the Yashica Electro 35 show the exposure warning lights. An oddity about this example is that the film speed dial goes from 25-1000 instead of the normal 10-400 ASA for this model. Perhaps it was upgraded at some point.

Yashica Lynx-14

The Yashica Lynx range was a series of rangefinder comparable to the Electro 35 range above, pairing fast high-quality lenses with easy-to-use camera bodies, but unlike the Electro 35, the Lynx range were fully manual exposure cameras. The top model amongst the Lynx was undoubtedly the 1965 Lynx-14, which sported an impressive Yashinon 45mm f/1.4 lens - as far as I am aware the fastest fixed lens to be put on a fixed lens rangefinder. Somewhat unusual compared to its contemporaries was that the Lynx-14 (as well as other models in the range) had its lightmeter mounted in the top housing next to the rangefinder instead of in the lens body. Hence, when using filters one had to adjust the exposure manually.

A Yashica Lynx-14 with its magnificent seven-element Yashinon-DX 45mm f/1.4 lens in Copal-SVE shutter. The little button next to the lens was used to activate the light meter, so if the light meter appears to be dead despite there being a working battery in the camera, try pushing this button :-) Thankfully, the shutter also worked without battery.

An updated version, the Lynx-14E, was introduced in 1968 and added IC-controlled manual exposure, which required an extra, larger battery, but did away with the light meter needle. Instead, 'OVER' and 'UNDER' indicator lamps in the viewfinder would guide the exposure. The great benefit of this system was that it did away with any mechanical parts such as the lightmeter needle, making it much more resistant to shock damage.

A Yashica Lynx-14E, which had the same lens and shutter as the previous version, but had integrated circuit logic build into its light meter system.

Yashica Half 17 Rapid

Another Yashica half-frame camera was the Half 17 Rapid. It was a compact modern-looking camera with sleek lines featuring a coupled lightmeter with automatic exposure. The lightmeter cell was integrated into the lens mount. The camera sported a fast Yashinon 32mm f/1.7 lens. The camera was perhaps let down by the lack of a rangefinder, although the reduced depth-of-focus of half-frame cameras made this less of an issue than it would have been on a full frame camera with a similarly fast lens. As the name indicated, the camera used the Rapid cassette system (see Minolta Rapid 24 for details). The camera had a thumb wheel to advance the film instead of a wind lever. It was succeeded by the Half 14, which had an even faster f/1.4 lens as well as a CdS lightmeter.

A Yashica Half 17 Rapid with Yashinon 32mm f/1.7 lens.

Rear view of a Yashica Half 17 Rapid with an uptake cassette loaded. Note the small film frame and the thumb bottom left for film advance.

Yashica J-5

Yashica is not particularly well known for their SLR cameras, but they did produce several different ranges of them. The J range was equipped with the popular M42 lens mount, as opposed to the Yashica/Contax mount on later Yashica SLRs. The J-5 introduced in 1964 had an auto-return mirror and a top shutter speed of 1/1000, but was manual exposure, having an uncoupled CdS lightmeter with two sensitivity settings. No exposure information was shown in the viewfinder. The lens mount featured auto stop down of the aperture. The J range was later continued as the TL range, which featured through-the-lens metering.

A Yashica J-5 with Auto Yashinon 55 mm f/1.8 lens. Yashinon lenses were made by the Tomioka Optical Company, which became a subsidiary company of Yashica in the late 1960s.

Top view of a Yashica J-5 showing the various controls. The lightmeter would show the aperture required for the selected shutter speed, like a shutter-priority exposure mode, but this reading needed to be transferred to the lens by hand.

GAF Anscomatic 726

The 1966 GAF Anscomatic 726 was reportedly made by Petri, a Japanese camera specialising in small compact cameras as well as SLRs, so that is why this camera is listed here. GAF was the new name of the original Ansco company in the USA, which itself was a subsidiary of Agfa after it was bought out in 1928 (see also Ansco Karomat page). They sold many cameras under license. As far as I am aware Petri did not make any 126 format (Instamatic) cameras, so I can only assume they build this according Ansco's designs.

Considering the 126 format films were generally pretty terrible, the Anscomatic 726 stood out amongst the bunch. It had a parallax-corrected rangefinder, a coupled CdS lightmeter with auto exposure, a decent speed lens, a good range of shutter speeds up to 1/500 and a socket for flash cubes to finish it off.

A GAF Anscomatic 726 that's got its fair share of bumps and bruises with an Anscomatic 38mm f/2.8 lens. This is one of the lenses which has the questionable honour of being listed as radioactive by Oak Ridge National Laboratory in the USA due to the high amounts of thorium present in the glass. Thorium lenses are now banned but the radiation dose from these lenses was in fact very low.

Olympus Six

Olympus might not be as well known for its cameras as Canon, Nikon or Minolta, but it has been a big player in the Japanese camera industry for a long time and is still successful today. In fact, it is still producing digital versions of its old product lines such as the OM and the Pen, even reviving some of the classical lines of these cameras. The value the company puts on its history is clear from its well-documented Olympus Museum site.

The company has a long history which, as for many Japanese camera makers, already started before WWII as an optical company. It then diversified into camera lenses as well as then-popular medium-format folding cameras. The first model of these was the 6x4 format Semi- Olympus, whilst the company was still named Takachiho. If you're interested in the details, this site has more than plenty! Shortly afterwards followed the Olympus Six, a 6x6 folder for 120 rollfilm which could also be used in the original Semi 6x4 format by using a film frame mask. It had markings on the viewfinder and an extra red window at the back for this. A more elaborate version, the Chrome Six, which included models with a coupled rangefinder, was introduced after WWII, and stayed in production until the mid 1950s, by which time Olympus changed its focus to 35mm, with which it would become incredibly successful.

An early wartime variant of the Olympus Six with Koho shutter and Zuiko-S 75mm f/3.5 lens, which indicates this example is a Super Olympus II. The original leather has been replaced, so this name is no longer indicated on the back of the camera. The Zuiko-S lens is of an unusual five-element construction, apparently due to difficulty sourcing optical glass during WWII. These cameras were produced during WWII until 1943.

Olympus 35

The Olympus 35 was introduced in 1948 and was the first 35mm camera by Olympus. It was small but remarkably heavy for its size, and the design of the top plate was clearly inspired by the Leica I viewfinder camera. However, the Olympus 35 was equipped with a leaf shutter and had a fixed lens. The very first model had a 24x32 film frame, just like the Minolta 35 Model A, but this was soon extended to the more regular 24x36. It was equipped with a 40mm f3.5 lens, an unusually wide lens for a 35mm camera, and perhaps related to its original film frame size, as 40mm is exactly the length of its diagonal, the measure commonly used to define standard focal length.

The first Olympus 35mm camera was the Olympus 35; the variant shown here is the model IV, the first variant where the shutter release and cocking mechanisms were internal to the body, making the camera look cleaner than earlier models, which had external linkages.

Top view of the Olympus 35, note the Leica I-inspired controls such as wind knob, rewind knob, shutter release and control lever. In addition to A(dvance) and R(ewind) settings the latter also has a D(ouble exposure) mode, a nice little feature I haven't seen on many other cameras.

A redesigned model called the Va was introduced in the mid 1950s and had a one-piece top housing and larger wind knobs, it also had a hinged back instead of the removable back of earlier variants. Shortly after a version with rangefinder, wind lever and automatic shutter cocking was introduced: the Olympus 35-S. Produced in parallel was the very similar 35-K, although the name on that camera still simply was 'Olympus 35'. A wide angle lens variant, the Olympus Wide with 35mm lens (instead of 40mm, the regular version was relatively wide already!) was introduced around the same time (see below).

A later variant of the Olympus 35, a 35-K with D. Zuiko 40mm f/3.5 lens. One unusual feature is that the complete lens assembly was in front of the shutter, a construction typically only found on cameras with interchangeable lenses. This is different from the original Olympus 35, perhaps it was easier this way to implement the rangefinder coupling.

Olympus Wide-E

The Olympus Wide range was introduced around the same time as the Olympus 35-S, so predates the 35-K above. Its main feature was the 35mm lens, a wide angle lens, hence the name, although not much wider than the 40mm lens on the regular Olympus 35. Only few camera makers made 'Wide' variants - Minolta, Ricoh and Walz were the main others, which has always surprised me a little as these cameras are perfect for snapshots.

The first Olympus Wide model had a wind knob and lacked a lightmeter, but the Wide-E shown below had a rapid wind lever as well as a selenium cell. A desirable version with faster f/2.0 lens instead of the f/3.5 lens on the other models was called the Wide-S, but it lacked the lightmeter.

Olympus Wide-E with D. Zuiko 35 mm f3.5 wide angle lens and diffusor attached to the lightmeter cell.

Top view of the Olympus Wide-E. Note the exposure dials integrated with the rewind knob.

Olympus Auto (Electro-Set)

In the late 1950s Olympus modernised their camera line-up once more and introduced a rangefinder with exchangeable lens mount, the Olympus Ace, as well as a similarly styled model with fixed lens mount and lightmeter, the Olympus Auto. This was the first Olympus camera with semi-automatic exposure control: it would choose a shutter speed for a certain aperture or the other way round.

An Olympus-Auto Electro-Set with E. Zuiko 42mm f/2.8 lens. A faster f/1.8 version was also available.

Olympus-S

Although probably better known for its Pen range and the OM SLR range (see below), Olympus did produce several impressive full-frame 35mm compact cameras, including the Olympus-S and 35 SP (see below for the latter). The Olympus-S was quite similar to contemporary Japanese rangefinders such as the Minolta AL or the Konica S. The original version was marked 'Electro Set' and had a selenium cell lightmeter, but this was soon replaced with a smaller and more reliable CdS cell. It most impressive feature was probably its seven element f/1.8 lens Zuiko lens with a relatively short 42 mm focal length.

One of the lesser known Olympus cameras, the Olympus-S with G. Zuiko 42 mm f1.8 lens.

Olympus 35-LC

The Olympus-35 LC was very similar to the Olympus-S above, but had the lightmeter CdS cell positioned above the lens within the filter ring, so that when you mounted filters the exposure would automatically be adjusted. The lens was slightly faster (f/1.7 vs f/1.8) so presumably the optical formula changed somewhat. It was a fully manual exposure camera, the lightmeter needle showing in a window at the top of the camera as well as in the viewfinder.

Olympus 35 LC with G. Zuiko 42 mm f1.7 lens, very likely the same lens as on the Olympus-35 SP below.

Olympus-35 SP

The Olympus full-frame 35mm range also included one of the best compact rangefinders to be ever build, the 35 SP, introduced in 1969. It was the top model of the Olympus 35 range, equipped with a superb fast seven-element f/1.7 lens, automatic as well as metered manual exposure modes and an excellent rangefinder. It even had a spot meter function (from which it derived its name) and it still worked without battery, unlike many of its competing models, like the Konica S3 and Minolta Hi-Matic 7sII. Due to these features it is still highly popular and commands good prices, but if you can afford one, do get one!

Olympus 35 SP with G. Zuiko 42mm f1.7 lens.

|

Detail of the rear of the Olympus 35 SP showing the button to activate spot metering, which is how the SP got its name.

|

Olympus Trip 35

The Olympus Trip 35 was introduced in 1967 and was a 35mm automatic exposure camera that didn't need a battery to work. This wasn't anything new, see e.g. the earlier Minolta Hi-Matic, but the Trip 35 did it in a small and easy to use package. It lacked a rangefinder and relied on zone focussing so was very much a point and shoot camera. The auto exposure system had two shutter speeds, 1/200 and 1/40, and it would choose the slower one unless this lead to an aperture of f/11 or smaller, at which point it would switch to 1/200. It also had an option to partially override the automatic exposure system by selecting a specific aperture setting, this would set the maximum aperture the camera would use during auto exposure at a fixed shutter speed of 1/40. Thus, depending on the light conditions, it could still chose a smaller aperture. If you were to select a too small aperture, the camera would under-expose.

This camera has become a bit of a cult classic as it's rather foolproof and easy to use, lightweight and can't run out of batteries, plus the lens has the reputation of being very sharp.

Olympus Trip 35 with 40mm f/2.8 lens, so quite a wide standard lens which was a long Olympus tradition. Lens focus and aperture settings were shown in the corner of the viewfinder.

Olympus Pen-F / Pen-FT

One thing Olympus has always been known for is its fondness of small, well-constructed cameras, and its half-frame range of Olympus Pens were the prime example of that. Its most iconic member was the Pen-F, a half frame SLR with interchangeable lenses. It was introduced in 1963 and featured a rotary titanium shutter with a maximum speed of 1/500s. In contrast to most other SLRs, its mirror swung sideways, probably to do with the fact this was a 'portrait camera', i.e., its film frame was in the portrait position. The viewing image was projected into the viewfinder in the correct orientation through a set of prisms and mirrors, which avoided the typical pentaprism hump one finds on most SLRs, but did result in a somewhat reduced brightness.

An original Olympus Pen-F with F. Zuiko Auto-S 38mm f/1.8 lens, which was the standard lens for this model, it being a half-frame camera (18x24mm).

Several models were produced. The first was the Pen-F itself, easily recognisable by the gothic-style letter 'F' engraved on the front (shown on the right). Next was the Pen-FT, which was a single-stroke camera (the original Pen-F was double stroke) and featured a coupled lightmeter system. The Pen-FV was similar but without lightmeter. A few medical cameras for use with microscopes were also produced, these lack the ground glass focussing screen, and some had round film frame masks. |

|

| |

The Olympus Pen-F came as a system with a range of excellent, compact lenses, making this a very small package indeed, ideally suited for street photography and the like. The lenses ranged from 20mm up to super telephoto lenses and included several zoom lenses, as well as ultrafast 42mm f/1.2 and 60mm f/1.5 lenses. |

An Olympus Pen-FT with E. Zuiko Auto-T 100mm f/3.5 lens mounted. I noticed that different lenses had different letters in front of Zuiko and worked out that it probably represents the number of elements in the lens, starting with A for 1. This means the F. Zuiko was a six-element lens whereas the E. Zuiko had five elements.

I had the pleasure of taking a Pen-F apart for a client and was impressed by the modular design of the camera, which make it easy to separate the mirror box, shutter assembly and camera body, respectively. A true marvel of fine mechanics!

(left) Front view of the Olympus Pen-FT body, with the sideways mirror visible inside the lens mount. The lever to the right of the 'F' in Pen F is the selftimer; (right) Rear view showing the inside of the camera. Note the half frame format (18x24mm) and the metal shutter.

Olympus Pen-D / Pen-D3

In addition to the Olympus Pen-F range with their interchangeable lenses, described above, there was a long-lived range of various fixed-lens Olympus Pen cameras. They were small cameras that would easily fit into your pocket, and most had similar design features such as a thumb wheel film advance and a removable back, and differed in shutter - lens combinations, lightmeters and exposure control. The Pen-D range was characterised by having high-quality fast lenses and uncoupled lightmeters. The original Pen-D had a selenium lightmeter and a six-element f/1.9 lens, whereas the Pen-D2 had a CdS lighmeter instead. The Pen-D3 had a faster f/1.7 lens.

An Olympus Pen-D with F. Zuiko Auto-S 32mm f/1.9 lens and Olympus-build shutter with a speed range of 1/8 to 1/500 s.

(left) Top view of the Pen-D showing the uncoupled lightmeter as well as the frame counter, which would go all the way up to 72 as this was a half frame camera after all. For those who service their own cameras, the screw with two holes on top of the frame counter unscrews clockwise. (right) inside view of the Pen-D showing the vertical film frame.

An Olympus Pen-D3 with F. Zuiko 32mm f/1.7 lens next to a film cartridge to show its compact size. The selenium cell of the original Pen-D had been replaced by a much smaller CdS cell, which was activated by pushing a small button at the back of the camera, but it did need a battery to work. The location of the battery compartment isn't immediately obvious, as it is located underneath the wind spool, inside the film compartment, so the battery had better not ran out with film already loaded!

Olympus-Pen W

The Pen W was another variant of the rather extensive Olympus-Pen range. Presumbaly the 'W' stood for Wide Angle, as it was equipped with a wide angle lens. Like other Pens, it had a thumb wheel for film advance and manual exposure controls on the lens. It focussed down to 2 ft and had a viewfinder with frame lines.

This is one of the rarer Pen models and desirable because of its lens, which makes it great for street photography, helped of course also by the tiny size of the camera. It's also one of the few Pens available only in black, adding to its mystique as well as its price on the second-hand market.

An Olympus-Pen W with E. Zuiko Auto-W 25mm f/2.8 lens, which in focal length was roughly similar to 35 mm wide angle in full frame format. Note the brassing on the edges of the camera where the paint has rubbed off. I have seen this on quite a few Pen-W, so either they were heavily used or the black paint wasn't of the highest quality.

Olympus OM-1

Olympus was relatively late in the SLR game, introducing its first full frame model, the OM-1, not until 1972, 10 years after Olympus' first venture into SLR with the iconic half-frame Olympus Pen F (shown above). The OM-1 was claimed to be the lightest and smallest 35mm SLR camera at the time. It was originally called the M-1 but Leica objected to this and forced Olympus to change it. The OM-1 was a fully manual SLR and also mostly mechanical instead of electrical (and thus worked fine without battery!) but did have a through-the-lens metering system. A welcome additional feature was the mirror lock-up to avoid vibration in long exposure photographs.

The OM system lens line-up was excellent and included many specialty lenses such as tilt-shift, macro and superfast prime lenses. Due to the OM-system's popularity, lenses and camera bodies are plentiful today and, other than specialty items, very affordable, so a good choice for the budding film photographer.

An Olympus OM-1 with F. Zuiko Auto-S 50mm f/1.8 lens. Unfortunately it was working properly, it fires but always at the same speed. After opening it up it turned out that the shutter settings are operated through quite a complicated mechanism involving various string and pulleys, and hopes of an easy fix faded quickly. It's now waiting on the 'it will take a few days' shelf.

Olympus OM-2N

The Olympus OM-2 was introduced two years after the OM-1 and added an automatic exposure system to essentially the same body. It featured through-the-lens metering but needed a battery to work. An updated model with improved flash functions, the OM-2N was introduced in 1979.

An Olympus OM-2N MD with G. Zuiko Auto-W 28mm f3/.5 wide-angle lens.

The same camera here shown with 75-150 mm f/4 telezoom and 200 mm f/4 telelens, which were relatively small, just like the camera itself.

Olympus OM10

The 1979 OM10 was Olympus' first consumer grade SLR. It was an aperture-priority automatic exposure camera. It was light and easy to use, and a big success. The main complaint was the lack of exposure control, for instance for exposure compensation one had to adjust the ISO dial. However, a manual adapter was available which allowed fully manual operation.

An Olympus OM10 SLR camera with its standard Zuiko Auto-S 50mm f/1.8 lens and manual adapter fitted. The most mysterious part of this camera is the little bitcode thingy on the front just below the shutter button. No clue what it means, it's the same on all OM10s and it only appeared on this model I think.

Top view of an Olympus OM10 showing the various controls. Note that what looks like a shutter speed dial is in fact a film speed dial, as this camera does not have a speed dial; the auto exposure system selects a speed for you. Only by installing the accessory manual adapter (visible above the rewind knob) can one override the auto exposure system.

|